By a commentator for Tjen Folket Media

This text is an edited and abridged adaptation of the Norwegian Wikipedia article on Mossadegh and the coup in Iran in 1953.

The coup and its pretext are relevant and interesting in today’s context. It is also relevant to view it in connection with the situation in Afghanistan, which we have written about earlier in the following article:

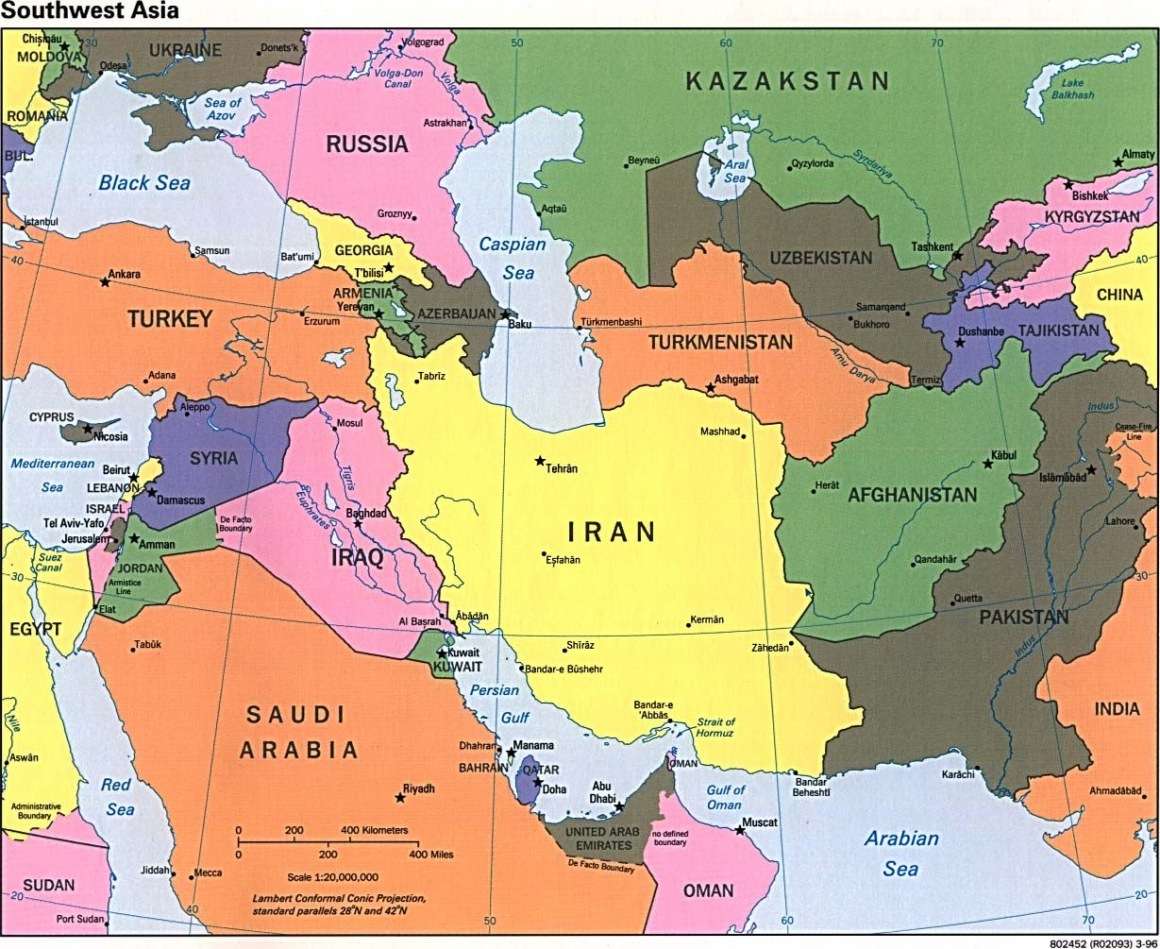

Afghanistan and Iran are neighboring countries and the region has for 200 years been the stage of this game, or competition, between Russian and British imperialism – with the exception of the period between 1917 and 1956 when the Soviet Union was socialist – along with, eventually, US imperialism. And to a lesser degree, smaller imperialists like France, Germany, China – and even Norway! – are active in the region. Yet both today’s heated situation and the history up until now shows that the US and Britain are in an especial engaged position.

Iran once bordered the Soviet Union, specifically the Soviet Republic of Turkmenistan. Today, Russia and Iran are both allied with Assad in Syria and the country is today among few countries with border access to the Caspian Sea.

Mossadegh was a state leader similar to many in the 1950s. All over the third world, a wave of anti-colonial struggle was waxing. In many places, revolutionaries and communists were in the leadership for revolutions. The anti-colonial struggle was objectively a part of the global revolution, but in many places, bourgeois forces took power. They were not in a position to consequentially break with imperialism and as a rule fell to to the imperialists’ game. Either they became traitors, or they were simply removed from power – like Lumumba in the Congo or Mossadegh in Iran.

Al-Jazeera: Iran’s Mossadegh ‘would have negotiated with Donald Trump’

The following is primarily copied and translated from the Norwegian Wikipedia article on Mossadegh.

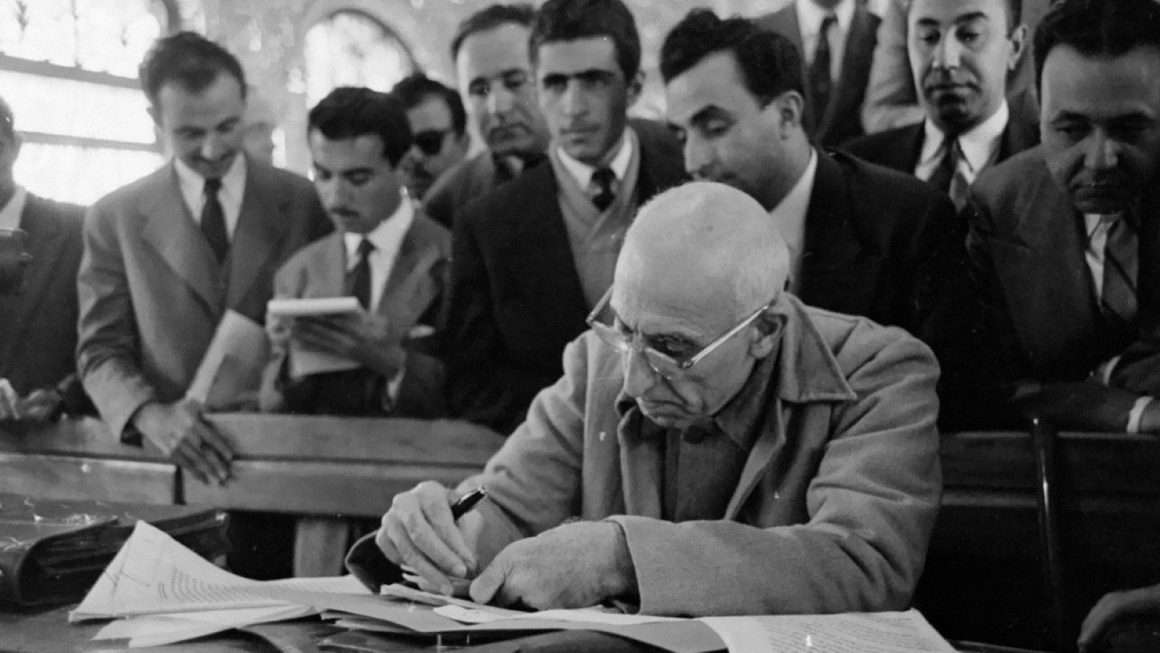

Muhammed Mossadegh was the Prime Minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953. He was removed from power by Muhammed Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, and his loyal forces in a complicated plot, supported by British and American intelligence services.

The Way to Power

After having received his education in France, Muhammed Mossadegh got his start in Iranian politics in 1914 when he was appointed as governor in the Iranian province of Fars by Ahmed Shah Qajar and received the title of Mossadegh by the Shah.

In 1941, Reza Pahlavi abdicated and Mossadegh was again elected to Parliament. This time, he ran as a member of the National Front of Iran (Jebhe Melli) that he himself established in order to end foreign presence in Iran after WWII, particularly that which was established to exploit Iran’s oil resources.

The Abadan Crisis

In March 1951, the Iranian parliament voted to nationalize Iran’s oil industry and take control over the British Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). Some time after, the National Council (Majlis) elected Mossadegh as the new prime minister. The young Shah had no choice but to accept Parliament’s decision. After taking office, Mossadegh implemented the nationalization of the oil industry. This led to the expropriation of the British AIOC.

The British government responded, in turn, by announcing that they would not allow the Mossadegh government to export oil produced in the earlier British-controlled factories. A fleet of British ships were sent to the Persian Gulf to hinder Iranian attempts to transport oil out of the country. An economic standstill followed, where the Mossadegh government refused all British participation in Iran’s oil industry, while Britain blocked exports of oil from Iran.

The Abadan crisis led the country quickly into economic difficulties. While Iran had earlier had an annual income of over 100 million USD in exports to Britain, the same oil industry led to the accumulation of Iran’s debt in nearly 10 million USD per month after nationalization.

Mossadegh remained popular after the crisis, and in 1952, he was re-elected for another term. He announced that he would ask the Shah for extended authority, including full control of the military and the Ministry of War. The Shah refused and Mossadegh tendered his resignation.

Ahmed Qavam was appointed as the new Prime Minister. The day he was appointed, he announced his intentions to resume previous relations with the British to end the oil crisis. This complete reversal of Mossadegh’s plans led to massive public outrage. Demonstrators from all political directions filled the streets, including communists and Islamists led by Ayatollah Kashani alike. Frightened by the instability, the Shah quickly removed Qavam from office and reinstated Mossadegh, giving him full control over the military as he had earlier requested.

Mossadegh gained an advantage due to his popularity and convinced Parliament to give him increased power, and to appoint Ayatollah Kashani as House Speaker. Kashani’s Islamists, in addition to the Tudeh Party, proved themselves as two of Mossadegh’s key political allies, even if both relations were often strained.

The Tudeh Party is an Iranian Moscow-revisionist party that was persecuted and nearly eradicated by the Islamist regime that took power in Iran in 1979. Before then, they had a strong position in the military, as many officers were Tudeh members, and were tightly allied with the imperialist Soviet Union.

Mossadegh quickly introduced several reforms. Attempts were made to replace Iran’s centuries-long feudal agricultural sector with collectivized land use and government-owned land areas.

The Plot Against Mossadegh

Mossadegh used his new power to kick out many of the top-ranking commanders of the army who were loyal to the Shah. The former officers were not willing to accept this and began to conspire against Mossadegh. They appealed to Britain and the US for aid.

The governments in Britain and the US had become increasingly concerned by Mossadegh’s reforms. They publicly denounced his policies as harmful to the country, and privately they both attempted to enter into lucrative oil contracts with Iran. But Mossadegh refused, and his close partnership with the Tudeh Party also sparked fears that Iran would become permanently allied with the Soviet Union.

In October 1952, Mossadegh declared that Britain was an «enemy» and cut all diplomatic relations with the country. In November and December that same year, the British heads of the intelligence service recommended to its US counterparts that the Prime Minister should be overthrown. The new American administration under Dwight D. Eisenhower and the British government under Winston Churchill agreed to work together to remove Mossadegh.

On April 4, 1953, CIA director Allen W. Dulles approved the expense of 1 million USD to be used for «any and all means that could ensure Mossadegh’s fall». Soon after, the CIA office in Tehran began a propaganda campaign against Mossadegh. Ultimately, according to the New York Times, American and British intelligence services met again in early June, this time in Beirut, and laid the final touches on the strategy. Shortly after, according to his later published report, the head of the CIA Office for the Near East and Africa, Kermit Roosevelt, Jr. (the grandchild of Theodore Roosevelt), arrived in Tehran to lead the plot.

The plot, known as Operation Ajax, entailed convincing Iran’s monarchy to use its constitutional authority to dismiss Mossadegh from his post, which he had attempted some months earlier. But the Shah was unwilling to cooperate, and it required far more convincing and many meetings before they were able to carry out the plan. Meanwhile, the CIA escalated its operations. According to Dr. Donald N Wilber, who was involved in the plot to remove Mossadegh from power in early August, the Iranian CIA operatives posed as socialists and threatened Muslim leaders with «harsh punishment if they were to oppose Mossadegh», and thereby gave them the impression that Mossadegh’s popular support was on the verge of falling apart, thus awakening resistance against Mossadegh within the religious community.

Mossadegh became aware of the plot and become more and more on guard against conspiracies within his government; Parliament was suspended indefinitely and Mossadegh’s «crisis of power» was deepened.

In Iran, Mossadegh’s popularity sank when the economy and the masses continued to suffer. The Tudeh Party ended its alliance with Mossadegh, along with the conservative clerical fractions.

To remain in power, Mossadegh understood that he would need to continue to consolidate his power. Since Iran’s monarch was the only person who had more power than him, according to the constitution, he viewed the 33 year old king as his greatest threat. In August 1953, Mossadegh attempted to convince the Shah to abandon the country. The Shah refused and formally dismissed the Prime Minister, in accordance with the foreign covert operation. Mossadegh refused to give in, and when it became clear that he was prepared to fight, the Shah fled to Baghdad, then to Rome, Italy. This was a security measure that was also a part of the British/American plan.

Observers speculated that it was only a matter of time before Mossadegh declared Iran a republic and established himself as president. This would make him the head of state and give him sovereign authority over the nation, which Mossadegh had earlier promised never to do.

Again, massive protests broke out all over the country. Anti- and pro-monarchy demonstrators clashed violently in the streets, which led to nearly 300 deaths. The pro-monarchy forces, financed by the CIA and MI6, quickly gained the upper hand. The military intervened only when the Shah-loyal tank regiments stormed the capital city and bombarded the Prime Minister’s official residence. Mossadegh turned himself in, and was arrested on August 19, 1953.

One of the leaders of the coup, General Fazlollah Zahedi, was appointed Prime Minister. The Shah himself quickly came back to Iran and returned to the throne. The attempt to remove him and the subsequent re-establishment of his power all occurred in less than one week.

Mossadegh was charged with fraud and sentenced to three years in prison. After his release, he was sentenced to house arrest until his death in 1967. The new government under the Shah entered into an agreement with foreign oil companies in August 1954 to «re-establish the flow of Iranian oil to the global market by considerable quantities».

Legacy

The scope of the Americans’ role in Mossadegh’s downfall was not formally acknowledged for many years, even if the Eisenhower administration was fairly clear about its opposition to the policies of the displaced Prime Minister. In his memoirs, Eisenhower writes aggressively against Mossadegh, and describes him as unpractical and naive, but never admits any covert involvement in the coup; however, the CIA’s role later became well-known.

During the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Mossadegh’s downfall was used as a unifying rallying point in anti-American protests. To this day, Mossadegh’s legacy in Iran is mixed.

In March 2000, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright issued an apology for Mossadegh’s overthrow: «The Eisenhower Administration believed its actions were justified for strategic reasons; but the coup was clearly a setback for Iran’s political development. And it is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America in their internal affairs.» The same year, the New York Times published a detailed report on the coup based on documents released by the CIA.

Kjære leser!

Tjen Folket Media trenger din støtte. Vi får selvsagt ingen pressestøtte eller noen hjelp fra rike kapitalister slik som rasistiske “alternative medier”. All vår støtte kommer fra våre lesere og fra den revolusjonære bevegelsen. Vi er dypt takknemlige for dette. Vi overlever ikke uten, og du kan gjøre ditt bidrag ved å støtte oss med det du kan avse.